Everything around us is designed. Products, services, laws, and policies, all are designed and they mediate how we interact, who’s (not) in charge, and who can(not) participate. Therefore, design is not and cannot be neutral. In other words, design is political, because it helps form the structures that distribute power and determine who has or does not have freedom of choice.

Design research increasingly pays explicit attention to the political dimension of design. Perhaps it’s the environmental crisis, the pandemic, or the war, that have more clearly shown us how much we depend on each other, on the systems we’ve built, and on the entire ecosystem that includes non-humans. In ‘proclaimed’ democracies, everyone should have an equal vote, but in practice, those with more power and resources often disproportionately influence decisions. Design decisions are no exception: those with implementation power - for example, companies and governments - may influence design decisions more than those who use the designs. Moreover, the increasing use of Artificial Intelligence, attention to designing for behavioural change, and the entanglement of networks among digital systems, all complicate our understanding of who influences what and how. In a similar vein, design researchers depend on research agendas that are built on mainstream ideas, such as the free market, maximum efficiency, and longevity. Against this backdrop, a better understanding of power structures and injustices that design might host or perpetuate has become a pressing concern.

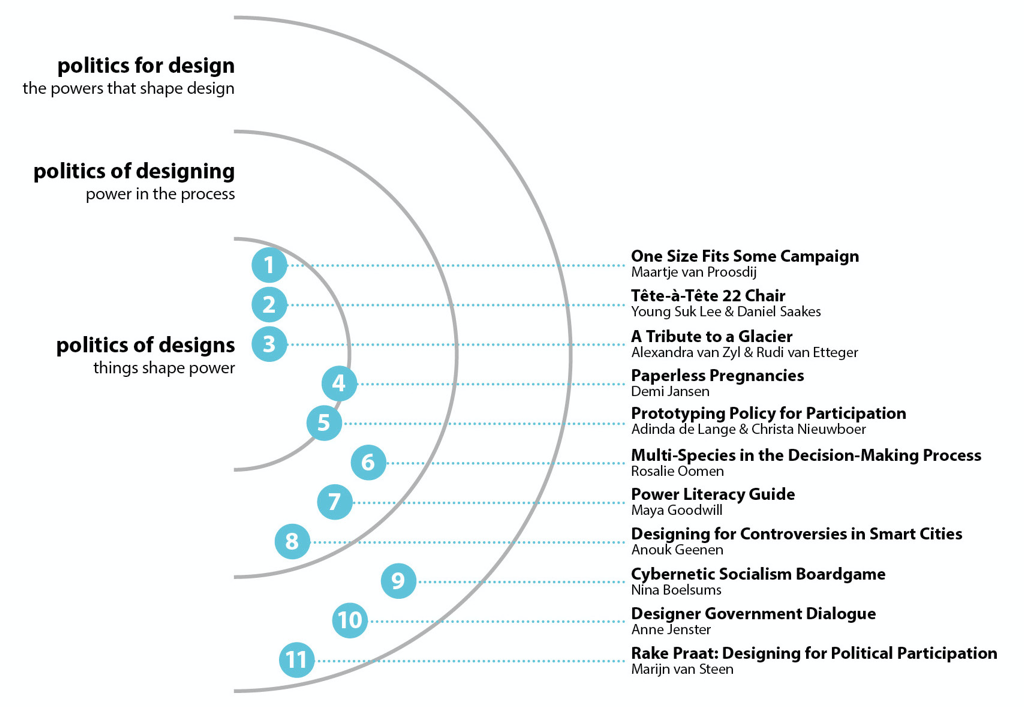

In this exhibition and design debate about the Politics of Design, we distinguish between the political influence of things (politics of designs), the process of designing (politics of designing), and the socio-political system in which design operates, which influences and is influenced by the actions of design researchers and practitioners (politics for design). Subsequently, we ask: How can design make sense of its existence – as a discipline and profession – in dealing with political questions and critique? How does design enable individuals gain or lose agency? What dominant processes cause humans and non-humans to be excluded from participation? How can designers ensure that voices are heard by those excluded from decision-making in design processes? And how can designers contribute and influence political agendas on a local, regional, national or global level?

The designs in the Design United Exhibition present examples of how designers and researchers approach the politics of design. For instance, Cybernetic socialism is a game designed to help policymakers and others think about a new economic world order, that of post-capitalism. One Size Fits All includes a campaign, thinking model, and collection of product examples to make aspiring design students sensitive to feeling excluded due to unconscious biases, in this case, gender roles. Tête-à-Tête 22 shows how a mundane product such as a chair can be viewed from a political perspective; in sitting, dependence is literally created, which means that cooperation is necessary and thus the power is also equalized. And you can find more examples on the website, addressing the different levels of politics of designs, politics of designing, and politics for design.

The range of projects we have included do touch upon but can never cover all nuances and complexities of the politics of design. Nevertheless, they jointly portray a meaningful picture that can stimulate debate and discussion on this increasingly distinct topic. We anticipate that they can point design researchers and practitioners to the political dimensions of their work.