Josh Snow, Kevin Shu Lai

The majority of the global human population resides in cities, for example, Amsterdam. In fact, by 2100, 85% of the world's population is projected to reside in urban areas. So cities will remain the places where most of us encounter complex and interconnected socio-ecological challenges. Soil contamination and organic waste management are two of these challenges.

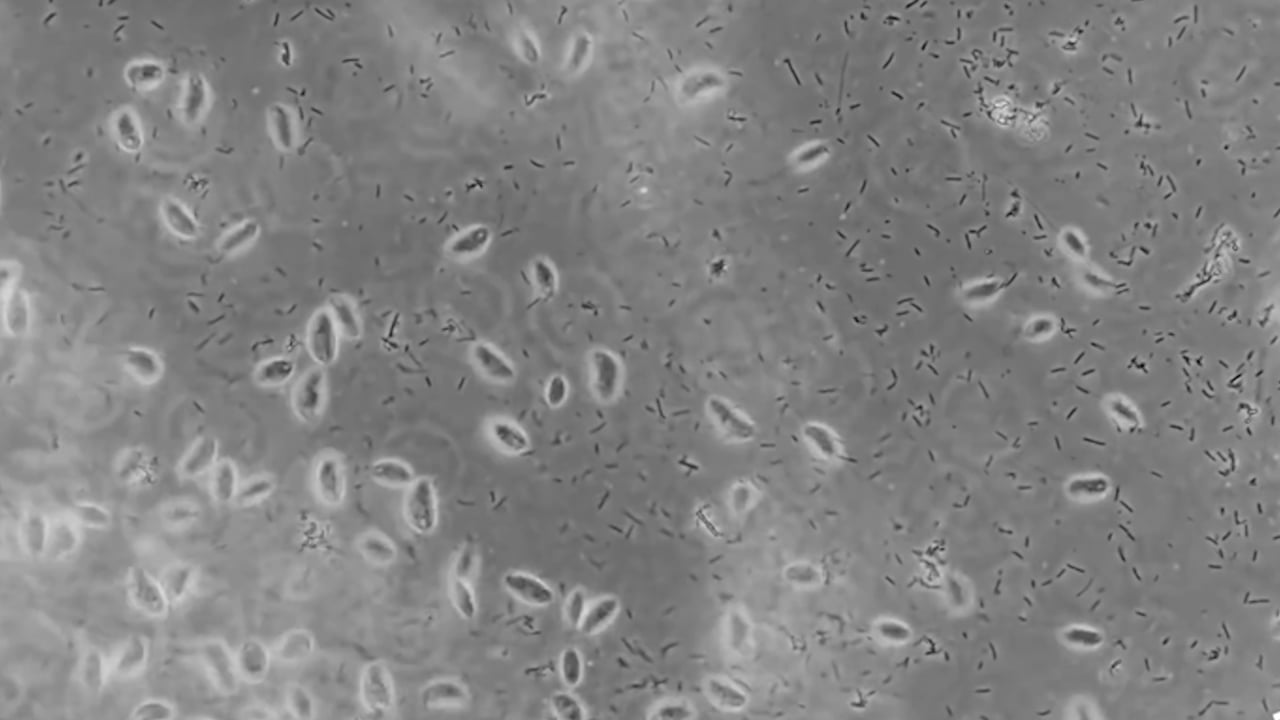

Soil stores more carbon worldwide than that contained in all the plant biomass above ground. Healthy soil prevents erosion and mitigates drought and flood due to its ability to absorb and store high quantities of water. Only recently has it become understood that soil requires continued care, urban soils included. But soil ecosystems, like so many other ecosystems, are under increasing stress from anthropogenic activity. Globally, over a third of Earth's soil is degraded due to industrialization and modernization processes, particularly through ongoing urbanization.

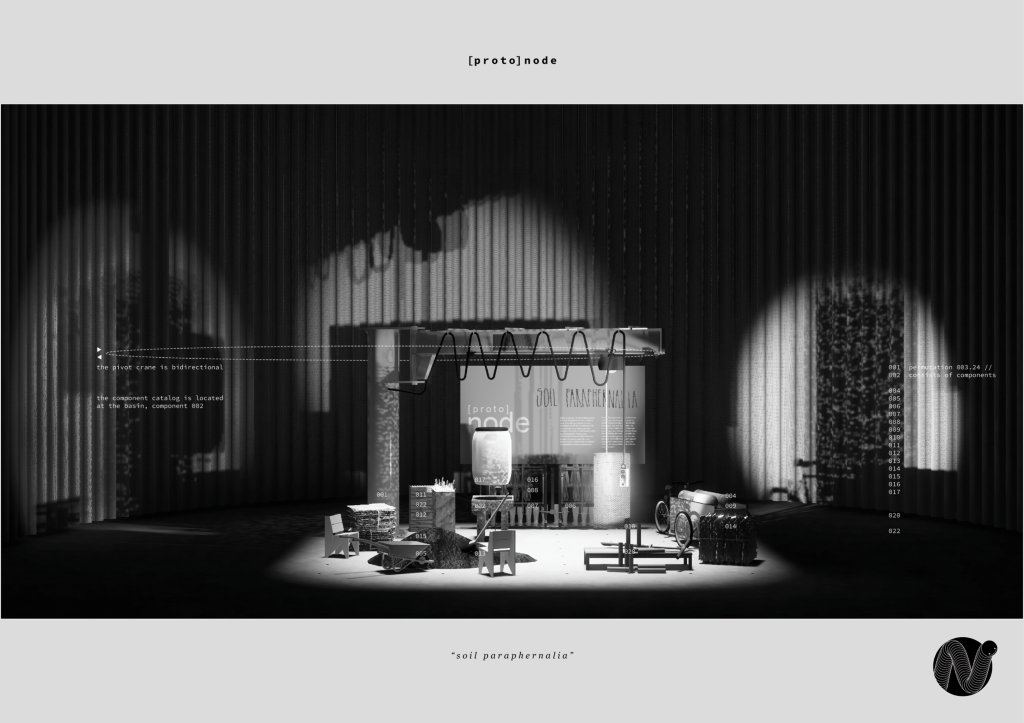

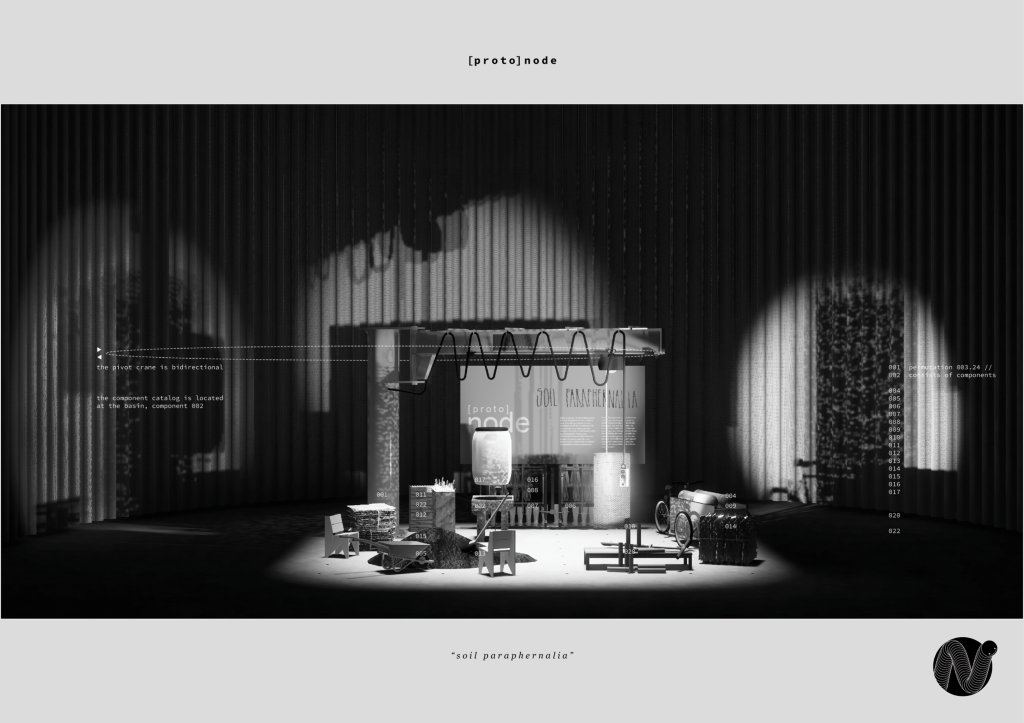

Recognizing soil's significance requires a paradigm shift in urban spatial planning and design. That is what the [proto]node helps facilitate. A soil-positive form of urbanization, what some have called a ‘multispecies urbanism,’ would not only lead to healthier soil (communities) but would also assist efforts to reduce emissions, improve the resilience of cities to climate change and adaptation, help restore biodiversity, and provide more open green space. What’s the future of architecture in a post-capitalist society?

There is currently no comprehensive organic waste management in Amsterdam. At the same time, urban soils are often contaminated. These are interrelated processes of urbanization, however their maintenance remains siloed. Soil remediation can be linked with organic waste management to form an integrated, holistic decentralized and community-based infrastructure network of soil care nodes that can improve urban soils, reduce pollution, and facilitate immediate socio-ecological transformation of urban systems.

Though there is much to (un)build, this project seeks to challenge the continued removal of soil from human habitats through centuries of modernization and industrialization, processes that have been premised on a set of technologies. These technologies encompass not only the physical apparatuses but also the social, economic and political mechanisms and systems that have led to our current moment of mass extinction, runaway emissions, deepening social injustices, and environmental degradation. However technology is not inherently destructive; rather, there are alternative permutations that can support regenerative models of coexistence. The node is one such technology, intentionally programmed to support a “thick conception of entanglement and coproduction, practised as an obligation toward mutual flourishing” (Shotwell, 2016) and for eventual obsolescence as our culture transitions toward a new “ecosophy” (Guattari, 1989).

Nodes remediate soil and manage organic waste; but they also foster community through ongoing events and workshops that bring the arts and sciences together, engaging a diverse audience on issues related to soil remediation and its connection to broader climatic, socio-ecological and socio-political concerns.

In this project, we critically examine the architect’s role, emphasizing a shift from Eurocentric, capital-intensive, and exclusionary practices toward a more inclusive approach. Architects can become facilitators of urban infrastructures that serve as platforms for urgent climate adaptation and mitigation discussions. These spaces promote collaboration and contestation, embracing discord as part of the process. They challenge us to address the complexities of urban soil care, considering the diverse interests of both human and non-human actors.