Our society is facing a number of great challenges which will require all of us to significantly change our lifestyle in the coming years. To support people in those transitions, next to systemic changes, new designs are required that intentionally redirect behaviour for the common good. Intentionally changing behaviour comes with a great responsibility, as designs that do not live up to their promises can – for instance – nurture false beliefs that people are doing good. Changing behaviour is something that takes a long time to materialise, and the effect is often not sustained in the long-term. This research investigated how to improve the critical assessment in order to anticipate the effects of a design.

First, a theoretical model was developed that conceptualises the elements that influence the long-term effectiveness of a design in changing behaviour. This is dependent on the level to which people adhere to the use of the design, which is fuelled by how appropriate the design is in their personal context.

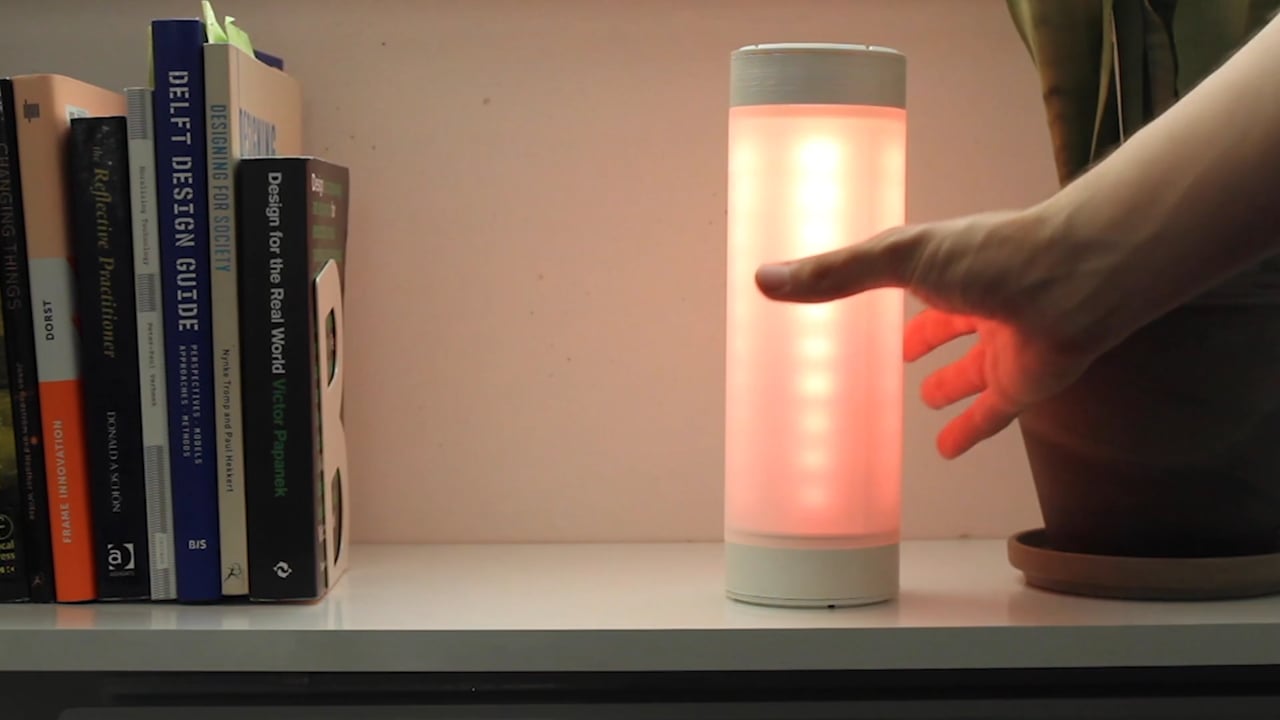

The relationships between the effectiveness and appropriateness were experimentally explored through deploying two research artefacts in the context of the end-user. These things, a bedlight and chatbot, aimed to harmonise people’s bed times in the same way by resembling the parental nudge to go to bed. However, through design and form-giving choices they differed in how appropriate they were in the context.

Through combining several qualitative and quantitative data sources concurrent insight was gained into the actual performance of the design as it is now and the elements that could be improved. This enabled the assessment of whether the design is proportionate and what the desired and acceptable level of persuasive influence is.

Design can help to support people in transitions to new behaviour, as artefacts can literally afford to do the right thing. Design for behaviour change often tries to force-fit behaviour of people to existing systems and structures. For effective behaviour change designers need to find balance between people’s experience of and the persuasive influence exerted by the thing. However, changing behaviour will always result in some friction as people are generally resistant to change. Designing things that are appropriate can help to ease that friction and stimulate the formation of a durable bond.

Through design and form-giving the designer can directly influence that appropriateness, by not conflicting with personal values and by being open to integration into our daily lives and practices.