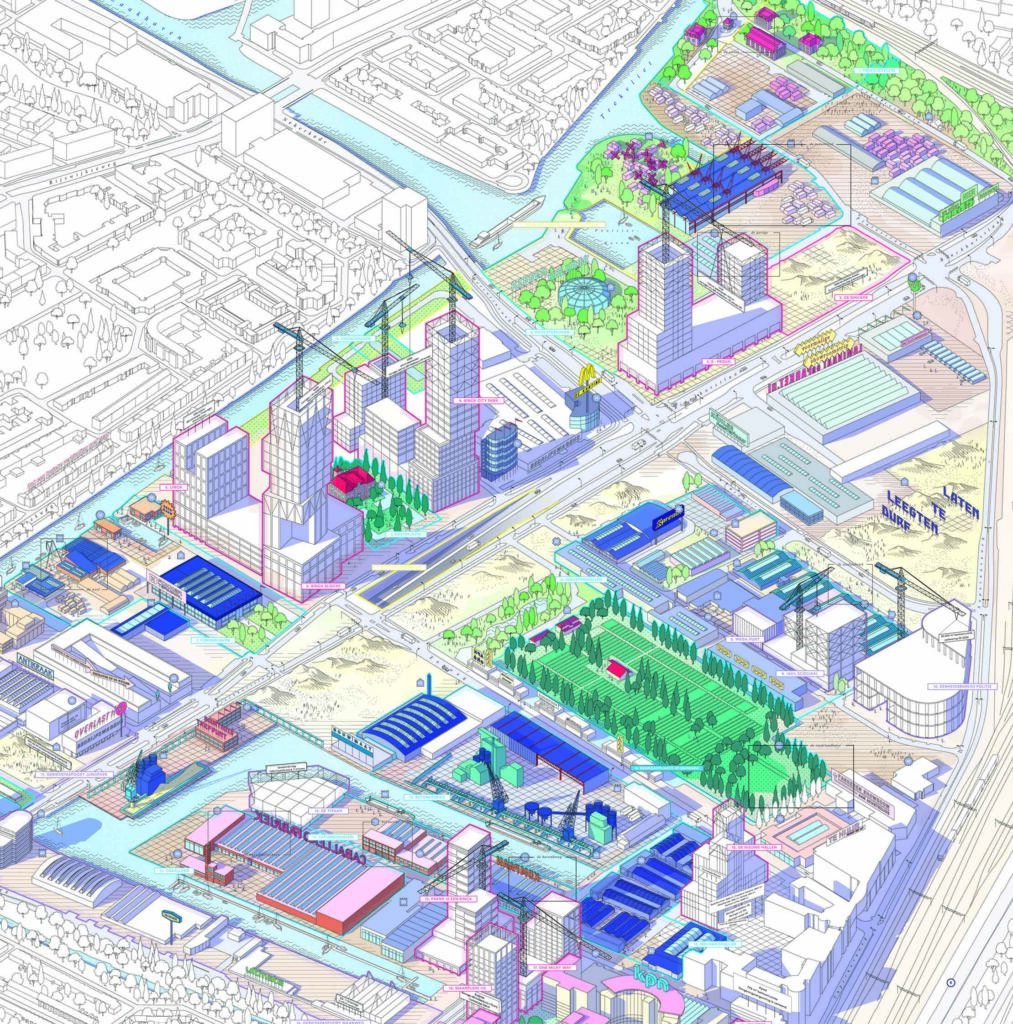

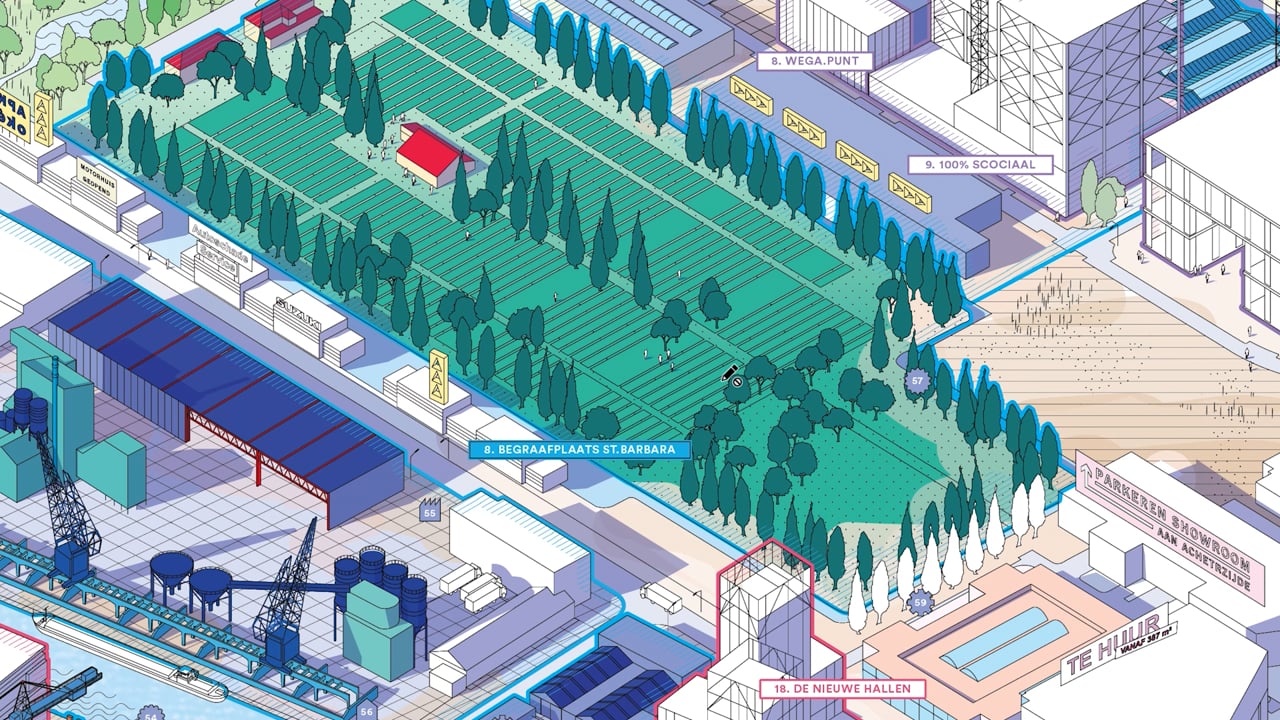

The Binckhorst is an industrial estate on the fringes of The Hague and home to a tight-knit community. The area has long been left untouched, but due to a housing deficit, The Hague’s council wants to extend the housing stock and develop the Binckhorst into a dense high-rise residential neighbourhood. Although the Binckhorst might seem an evident place to accommodate densification from ‘above’, the plans are controversial. The existing Binckhorst community fears the redevelopment plans will lead to a loss of their place-identity. Therefore, through a wide range of place-making practices, the community seeks to collectively sustain and develop their ‘place’ in the future. By creating four collaborative design-based interventions, this project contributes to the self-organisation of the Binckhorst community. Each intervention responds to the central place-making issues that emerged. The first intervention mapped which (in)tangible qualities of the Binckhorst were valued and (re)produced by its community, resulting in ‘a subjective atlas’ in order to contribute to the qualities’ appreciation and consolidation.

The second intervention aimed to unpack and comment on the place-politics through which the redevelopment was taking shape. This led to a dramatic visualisation of the past, present and future conflicts of place. Through the third intervention, the community collaboratively imagined a self-organisable future for the Binckhorst that could exist alongside the redevelopment plans. The fourth intervention aimed to (re)present, store and build the knowledge from ‘below’ into a living archive, in order to maintain an inclusive and democratic debate about the future of the Binckhorst.

In contrast to conventional participatory design projects, the ‘how, what and where’ of this project were not dictated from ‘above’ by a formal government, client or distant designer. Instead, the embedded designer had to take up alternative attitudes in order to contribute to the emergent and multiplicitous character of the civic initiative.

The embedded designer understands the difference between activism and taking-action; in this project the most effective interventions were not explicitly outspoken or loud. The designer is not concerned with what the Binckhorst looks like, but with how it works. The project engaged in the underlying generators of place, only when this is understood can interventions take place.