In the series TeamCaptains Then & Now, we talk with a former and current team manager of student teams within the 4TU Federation. Today: Project MARCH.

It’s lunchtime when I enter the Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) Dream Hall, where most of the university's student teams are headquartered. Students from each team convene at every level over some boterhammen–the Dutch word for sandwiches and a cultural staple.

Project MARCH is one of TU Delft’s student teams based here. Since its establishment in 2015, a new student cohort has developed an exoskeleton every year to help people with paraplegia walk again. Maica Brakkee, the current team manager, welcomes me warmly with a cup of coffee. Jelle Sturkenboom, captain of the first Project MARCH team, comes in a few minutes later.

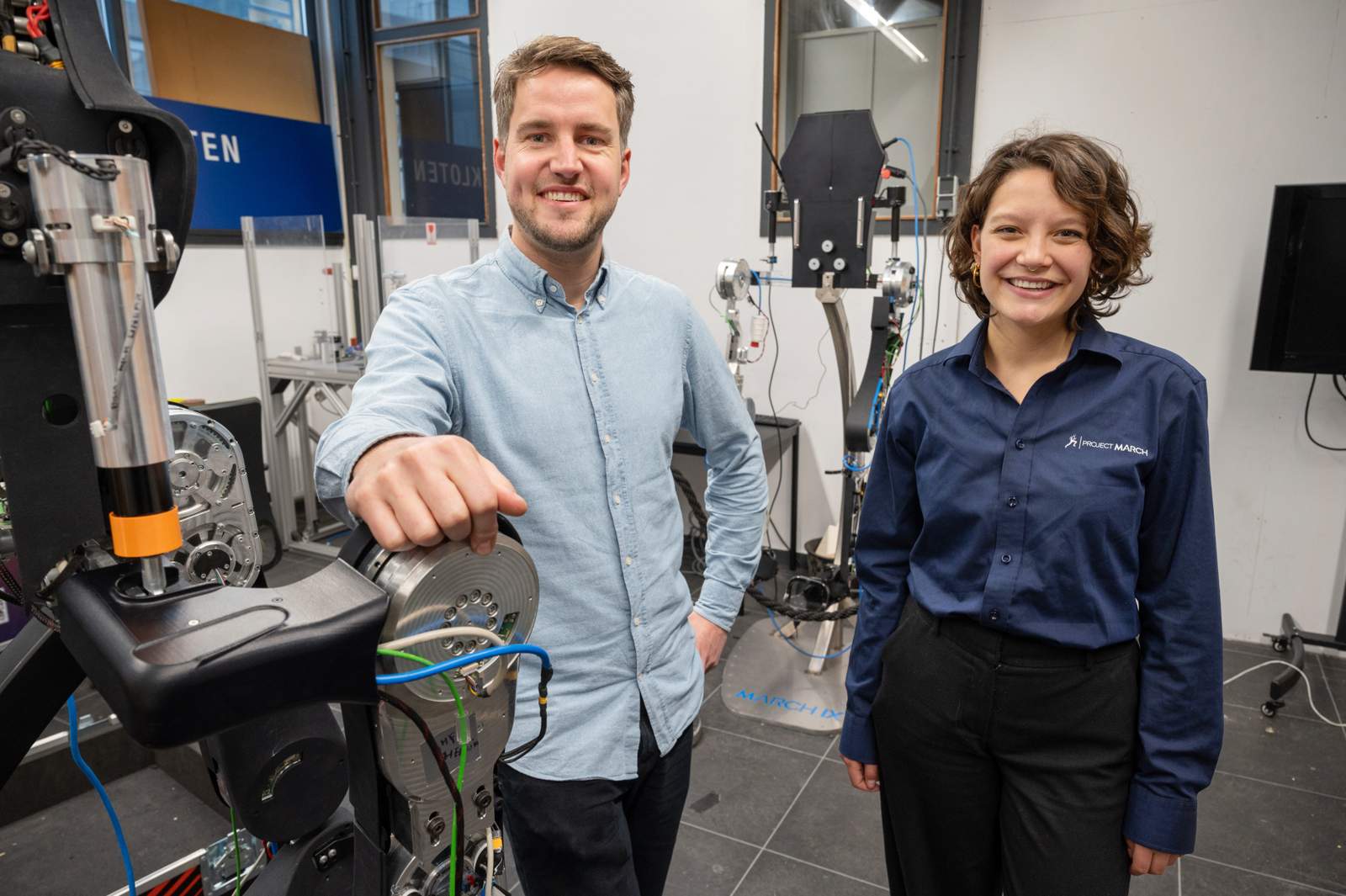

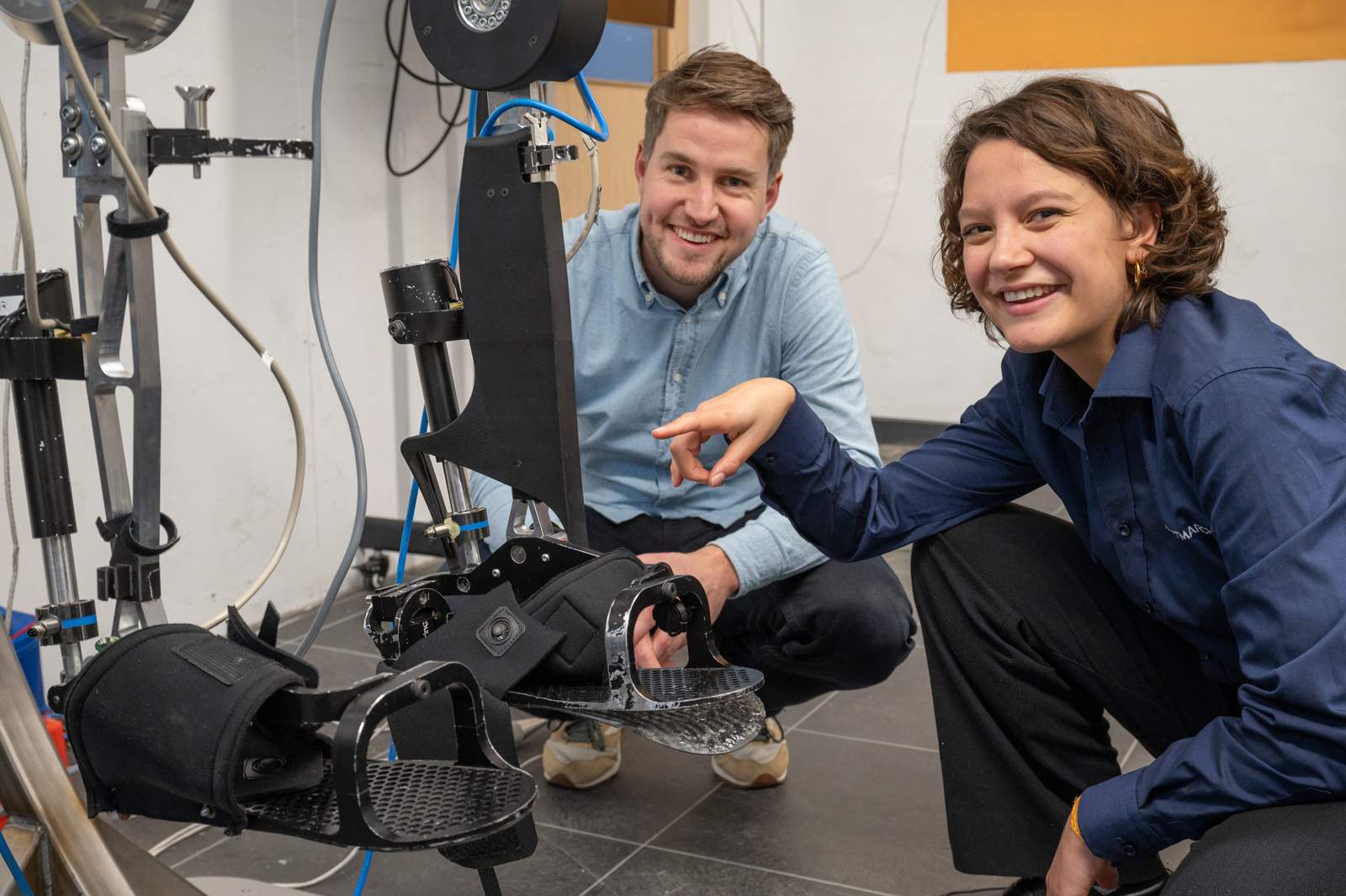

As Jelle also gets some coffee, we walk downstairs to the lab where exoskeletons are made. Bas Kijzers, the photographer, asks the two to pose with some of the previous cohorts’ creations. Although it is only the first time they have met each other, Maica and Jelle instantly click. Standing next to last year’s exoskeleton, the two start talking about design challenges, and the old captain catches up with the new one about the latest advancements in constructing high-tech walking supports. As the shooting is done, we walk to a meeting room.

The start of Project MARCH

“Although things have changed here, it still feels familiar; the smell in the workshop is exactly the same as it was,” says Jelle. During his university days, a decade ago, the Dream Hall was still there, but Project MARCH members still had to find their way there. Back then, the students had their first meetings in the library. A few months into the project, they could get a room in the building to house their headquarters.

An acquaintance told him about starting a student team designing an exoskeleton. So he joined a couple of interest meetings and was later asked to become the team captain, albeit being an “outsider”—the only architecture student on the team.

The social aspect involved with the team was what attracted Jelle. “While other teams were working on achieving a given speed, efficiency, or running a certain distance, Project MARCH is about putting effort into helping others. Combine it with a technical challenge, and things get even more stimulating.”

At its inception, Jelle had to take care of the practicalities–setting up a bank account, designing a logo, and finding a team name– but also of more complex aspects. “How do we develop the exoskeleton together with a person affected by paraplegia was one of the questions we initially asked ourselves. And also, ‘How is the TU Delft looking at our experimental testing with a person?’ It was a big snowball of things coming together,” he recalls.

The evolution of Project MARCH

Years later, Maica learned about Project MARCH during her bachelor's in clinical technology. One of her best friends and her partner were also members of previous cohorts. Captivated by their experiences, she applied for the team manager position and successfully landed the job.

As a master’s student in technical medicine, the student team aligned with her interests. Currently, this is her full-time occupation, as it is for most members of the team (26 in total) who decided to spend a year on the project.

To this extent, over the years, the team evolved into a more professional structure. In Jelle’s cohort, only 7 of the 22 members worked full-time. The student team is now divided into different departments, each with its lead who reports to the team manager. In addition, the student team now has easy access to a management consultant, who helps the team board make decisions and provides extra support.

A goal drives each student team

An essential part of a student team's activity is setting a goal. The first cohort aimed at the very ambitious goal of having their pilot—the paraplegic who tests the exoskeleton—stand up and walk. The starting point was the MINDWALKER exoskeleton. From there, the students started working on improvements to this system, focusing on knee, hip, and abduction joints. Despite all the hard work, the team didn’t build a fully functioning exoskeleton. Yet, their pilot Claudia could successfully stand up with the exoskeleton– still a huge achievement.

Maica’s team will unveil the exoskeleton design in March. “Last year, the team’s concept introduced invertible ankles, which worked passively. We want to add a motor to those joints to make them active. We are also changing some other joints to maintain maximum control.” Jelle likes the idea.

Project MARCH was founded to compete in the 2016 edition of the Cybathlon, a competition held in Zurich every four years. The Cybathlon challenges students from all over the world to develop assistive technologies for unpaired people. Since there will be no competition in 2025, this year’s team set a different goal.

“We thought how great it would be to allow a person affected by paraplegia to be part of a concert crowd. The goal is to have our pilot stand balanced without crutches– although they would be needed for walking ed.-- and be able to be part of a crowd and withstand everything that comes with it,” proudly says Maica.

Learning in a different way

Almost a decade later, Jelle works as a sustainability consultant for the Dutch government real estate organization (Rijksvastgoedbedrijf). Although his career went on another path, he still follows Project MARCH and has attended a few design reveals, noticing how many of the ideas his cohort had became a reality. His experience as a team manager stayed with him, teaching many valuable lessons.

On top of them all, there is resilience. “Everyone we pitched our idea to laughed at us, learning of the goal we set for ourselves. At the end of the year, we might not have realized everything we set out to, but we still achieved so much and surprised everyone. Even when people do not believe in your ideas, you just need to work hard to prove them wrong.”

The three months as a team manager have already been a great learning experience for Maica. “As much as I love studying, I am acquiring knowledge about how to work in a multidisciplinary team. You don’t become a good manager in a snap, and you need to figure it out on your own.”

Leading and being part of a student team

Rather than being directly involved in designing parts or finding solutions to technical challenges, a team manager is more of a coordinator, overseeing activities and providing the departments with what they need. Therefore, a team manager must be able to zoom out and observe the student team activities from an external perspective.

Jelle picked up this skill over the months, while Maica is still learning it. “I want to know everything and how things are going. It is easy to dive into the technical aspects of the project, but then, at the end of the day, as a team manager, you think: ‘What did I do today for the team?’”

The two team managers warmly recommend that every student consider joining a team. Jelle has a good metaphor. “The main point about joining a student team is getting the experience of running a company without having commercial goals to worry about. There is plenty of room to fail,” he says.

After my chat with the two team managers, I leave the meeting room. The building seems quieter now, and the tables where students had their lunch are empty. The buzz and enthusiasm are still there.