Sensors for a healthy lifestyle

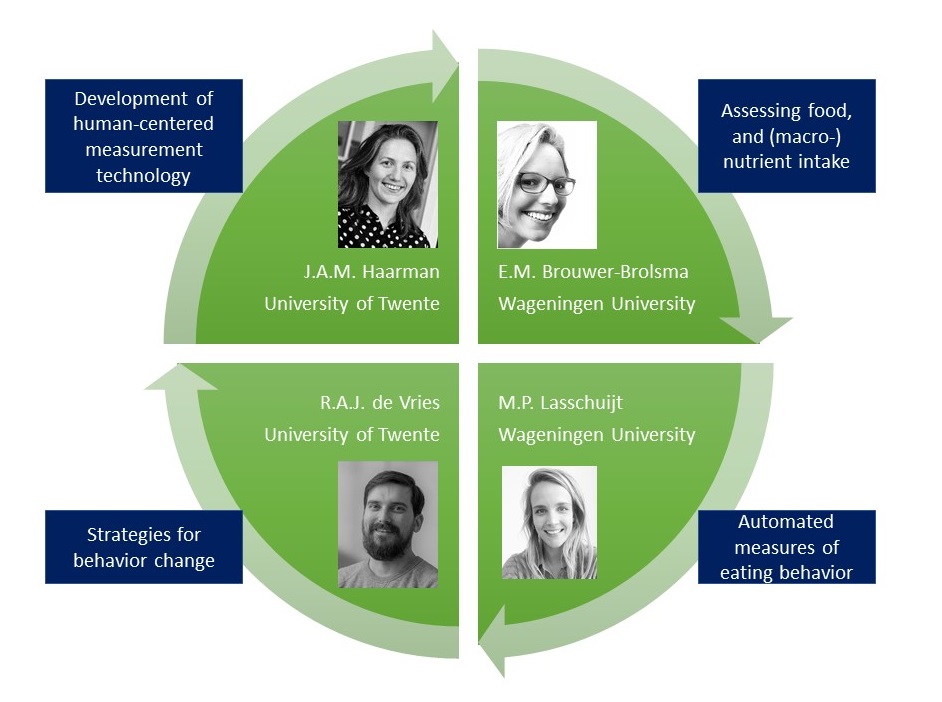

In the Food Intake project, part of the 4TU Pride & Prejudice programme, 4TU researchers want to use technologies such as sensors, smartphones and an interactive dining table to measure what, how much and how people eat.

Their aim is to gain a more accurate picture of our food intake and our eating behaviour, and ultimately to come up with interventions that get people to eat more healthily. The 4TU.Federation spoke to the four researchers in this project about their progress and the knowledge they each contribute from their own university.

What is the Food Intake project about?

Marlou Lasschuijt (WUR): in this project, we want to develop technologies to measure what people eat, and use this as a basis for developing strategies to ensure that people eat more healthily. To start with, these technologies are developed and tested in the eetlab (eating laboratory). Then they are tested in daily life situations so we can get a realistic picture of all the factors that play a role in eating behaviour, such as your surroundings, whether you eat alone, with your family or friends, watching TV or at the computer.

The classic form of monitoring food intake involves people keeping a diary in which they record everything they eat, including portion size, a method that is extremely prone to measurement errors. These may range from erroneously estimating portion size, forgetting to record items, or deliberately not recording unhealthy products from a sense of shame.

With this project, we want to see if we can use smart technologies to make food intake monitoring more accurate and less time-consuming, for example using wearables such as watches with sensors that automatically log when you are eating. Or that automatically take photos of what you are eating. This solves the problem of forgetting when you ate something and what it was. The wearable is linked to an app that stores all the data.

Elske Brouwer-Brolsma (WUR): Measuring what we eat sounds simple and there are already many apps on the market that can do this. However, very few of these apps have been validated, so it is questionable whether they can accurately quantify what a person actually eats. So this is one of the aspects we are looking to address in the app we are developing further in P&P.

In this project you are working together with all four universities of technology. What would you have been unable to do or achieve if just one university had had to do all this research on its own?

Marlou: Wageningen’s expertise is in the field of food and health, registering food intake, monitoring eating patterns and the aspects you need to take into account to be able to measure this accurately. So everything except the technology side, so that’s where we need the expertise of the other universities.

Elske: Including the expertise of TU/e. I already mentioned the app we are developing further in the P&P programme. For this we have engaged the expertise of Desiree Lucassen – PhD candidate at Wageningen University & Research and now also a researcher at TU/e. As part of her doctoral programme she is validating our app for reporting food intake. She is doing this by comparing the information that people enter via the app with the handwritten information they record in the traditional diary and with information from their blood and urine samples. By examining all these results side by side, we can see whether self-reporting tools such as this app give a sufficiently accurate measurement of what and how much a user eats.

We will use this information within Pride & Prejudice to look at how we can innovate the app yet further. Of course we already have ideas about this, and we have started several collaborations with TU/e, on aspects such as integrating photographs, crowd sourcing, artificial intelligence and what are known as conversational agents: systems that simulate human interaction.

We are also exploring collaborations with TU Delft more related to design aspects such as acceptability, user-friendliness and the attractiveness of the technologies.

Besides this, we need people with technical know-how, which is why we have entered into a collaboration with the University of Twente (UT), with the team of Juliet Haarman and Rutger de Vries and with Eindhoven University of Technology with Professor Lu Yuan and her team. UT is exploring whether the technological developments meet the needs of the user, how you can use technology to improve the ‘assessment’ of the food intake, and ultimately whether you can use it to bring about a change in behaviour.

Roelof de Vries (UT): You need both aspects – food knowledge and technological knowledge – to explore the full picture of the effect of technology on behavioural change.

What challenges does this project present?

Juliet Haarman (UT): It is very important to look closely at people’s natural behaviour in combination with their environment, and to explore just where technology can offer support in behavioural change. For example, you can look at how technology can make it easier and more fun to keep a food diary, but you can also take things a step further. Wouldn’t it be fun, for instance, if you could sit at a dining table that automatically registers what you eat or if there are any similarities with the diet of your fellow diners?

Roelof adds: The next thing is to make sure you use the right strategies that suit the situation. For example, we are looking at strategies aimed at the individual and at groups, and strategies aimed at the environments people move in, such as at home, at school and at work.

What impact has the coronavirus pandemic had on your research?

Marlou: The first studies were put on hold, which was a pity of course, but now we will be carrying out a study in November in which participants and researchers can maintain social distancing. Everything will be cleaned between testing sessions, and we have introduced walking routes in the lab to maintain distancing. So we’re completely coronavirus proof!

Roelof: We are also doing more research in the ‘virtual environment’, for instance, by getting people to evaluate a new technology in a virtual world. This provides a way for us to develop some ideas in advance and get feedback on them.

Elske: The positive thing about this period is that it seems to have made it easier to explore collaborations, because we’ve grown more used to video calling and this makes it easier to plan a preliminary meeting without having to set aside a whole day to meet around the table.

Why is this research needed?

Marlou: The population of the Netherlands is becoming more and more overweight. The BMI (Body Mass Index) is increasing, even in children. And our lifestyle is growing steadily less healthy, with an increasingly unhealthy diet and insufficient exercise.

Elske: With all the associated consequences for our health, such as glucose intolerance, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer, which in turn lead to increasing healthcare costs.

Will we start to notice this as citizens, and how soon?

Marlou: Yes, definitely. The aim is that in a few years’ time, we will have a technology that offers a hassle-free way of recording what and how you eat, so people can get personalised and targeted advice on how to eat more healthily, i.e. advice that fits their eating habits, enabling people to potentially stay healthy for longer.

A table packed with sensors and LED lights

At the University of Twente, an interactive table has been developed with sensors that measure weight distribution across the table. What meat and vegetables do people help themselves to, and how often? Is there a relationship to the behaviour of fellow diners? You help yourself to vegetables, do I do the same? The table is also fitted with LED lights in order to create opportunities for interaction. To give a simple example: a red light could appear around your plate if you help yourself to too much meat. But the technology could also be used to introduce an element of fun: you get a reward if you eat something healthy, like flowers that grow when you eat vegetables. This could encourage children who are picky eaters. Or we could use different colours. Colour has been shown to have a positive effect on people with dementia who usually have difficulty eating enough for their needs.

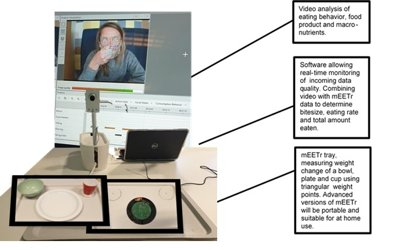

A smart tray

In order to study individual eating behaviour, researchers at WUR have developed a tray with an integrated weighing scale. The tray contains a plate, a dish and a glass, plus a camera focused on the face. This set-up is designed to measure how much you eat and how quickly. Could you, for instance, get people to eat more slowly by changing the texture of the food? This instrument offers a good way of monitoring people remotely. In November, we intend to link the data in this study to the data from the dining table, so that we can compare eating on your own to eating in a group, and eating under controlled laboratory conditions to a more natural setting such as an apartment.

The research team

Elske Brouwer-Brolsma

Wageningen University & Research

Division of Human Nutrition and Health

Elske.brouwer-brolsma@wur.nl

Juliet Haarman

University of Twente

EWI, Human Media Interaction

j.a.m.haarman@utwente.nl

Marlou Lasschuijt

Wageningen University & Research

Division of Human Nutrition and Health Sensory Science and Eating Behaviour group

Marlou.Lasschuijt@wur.nl

Roelof de Vries

University of Twente

Biomedical Signals and Systems group

r.a.j.devries@utwente.nl