The novel nature of quantum technologies

Quantum technologies are best understood as a family of technologies based on quantum mechanics. In short, quantum mechanics is a theory in physics describing the behaviour of particles at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles: a task that it performs stunningly well for over the last 100 years. Besides advancing our understanding of the fabric of reality, quantum mechanics can also be applied in technology development.

Quantum technologies exploit quantum principles like entanglement, superposition and tunnelling, for example to acquire, process and communicate information. Within the family of quantum technologies, we can roughly distinguish between three types, aimed at measuring physical quantities (quantum sensing), performing mathematical tasks (quantum computing) and the creation of networks (quantum communication).

In response to the potential impact of the quantum technology family, in terms of advancing and disrupting practices across multiple domains in science and society, the call has been made to proceed responsibly in quantum research and development (R&D). The field of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) has produced several accounts on what ‘proceeding responsibly’ entails in the context of new and emerging technologies. These accounts have largely been developed in response to technologies that fundamentally differ from quantum technologies with respect to their foundational principles.

Building on quantum mechanics, quantum technologies come with a certain (relational) view on the world around us: understanding it in terms of processes or interactions rather than objects and approaching properties not as ‘out there’ but as relative to an observer or a set-up for observation. Connecting these fundamental physical principles to the way we approach RRI may seem wrong-headed, perhaps even a category mistake. Nevertheless, the metaphysical implications of quantum mechanics may place our ethical considerations in general, and in particular those concerning RRI, in a different light. At least, it is worthwhile to explore whether the novel nature of quantum technologies could call for a revision of current RRI-approaches.

A process-based world view, a process-focussed approach to RRI?

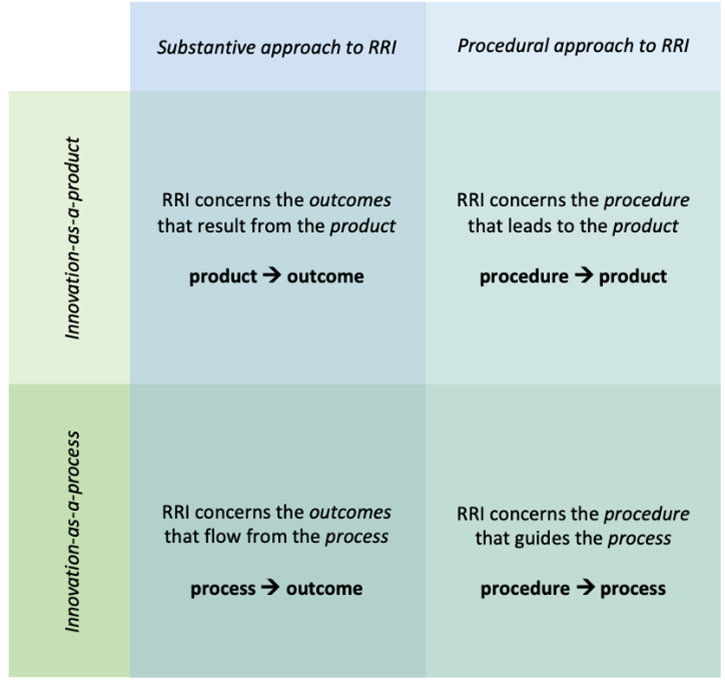

Within the field of RRI, there are two general approaches: a substantive or outcome-oriented approach and a procedural or process-oriented approach. Both are normative, although the subjects of their respective normativities differ. The substantive approach focuses on the outcomes of innovation, whereas the procedural approach focuses on process requirements. To make things a bit more complex, the concept of innovation itself can also be seen as either a product (innovation-as-a-product) or a process (innovation-as-a-process). Considering the two main RRI approaches and the two conceptions of innovation, a matrix with four possible approaches to RRI emerges (see figure 1). The question then is which variant best fits the nature of quantum technology – if any.

Figure 1. Four approaches to RRI

A first step in answering that question is to reflect on the kind of innovation that is here relevant: Should we characterize quantum technologies as innovation-as-a-product or rather as innovation-as-a-process? The answer seems to depend on our focus. A particular quantum sensing device may well be described as a product, while quantum cryptography or the quantum internet are better described as a process – performances rather than end-products. The nature of quantum technologies does not force us to adopt either conception of innovation in principle, nor is it unique in this respect.

Likewise, the internet can be convincingly described as both a product and a process, and so can AI. Quantum technologies have this duality in common with most digital technologies and software, rendering them “permanent semi-finished products”. Put differently, the nature of quantum technologies as processes at the micro scale does not require a process-oriented view of innovation per se.

"Quantum theory could be an inspiration for RRI"

What is more, this nature alone does not seem to call for either a substantive or a procedural approach to RRI. Acknowledging that we should best approach reality as processes of inter- and intra-action, for example, does not exclude the option of assessing the technologies that use quantum principles, from a substantive point of view. On a different level, quantum theory could be an inspiration for RRI, though. Just like physical properties – at least in the relational interpretation of quantum theory – are not absolute, existing by virtue of interaction between object and observer, we must acknowledge the non-static, context-sensitive character of values.

Moreover, it could also inspire epistemic modesty: just as in quantum theory it is fundamentally impossible to know precisely both the position of a particle and how its is moving, i.e. its momentum, so we should be modest about our abilities to both develop a useful new technology and anticipate its impact. Again, this is a metaphorical understanding of ‘uncertainty’, and not a deduction.

In the end, the choice between a substantive and procedural approach seems to depend on considerations that relate to the technology but are not necessarily implied by or inherent to the technology itself. Such considerations include the abilities of the actors involved (what can we do?), epistemic factors (what do we know?) and normative standpoints (what should we do?).

Fluidity in RRI

At first sight, quantum technologies do not, by their nature, seem to call for a specific approach to RRI. Which approach is best seems to depend, first of all, on the particular quantum technology, appealing to either a product- or process-based understanding of innovation. There may be good reasons to adopt a combinatory conception of innovation by default here: Taking both the product and process dimension into account and shifting accents depending on the technology at hand.

Furthermore, the choice between a substantive or procedural approach is misleading: a procedural approach without normative anchor points lacks orientation, while it is doubtful whether normative goals can be pursued without taking procedural dimensions into account. It thus appears that every meaningful and effective approach to RRI will have to integrate and balance substantive and procedural elements. The matrix should then be understood as a spectrum, which means that an appropriate approach to RRI is a matter of positioning ourselves within this field rather than adopting a specific quadrant. In this way, a more fluid approach to RRI is opened up, which may fit better the character of quantum, and other, technologies.

"Every meaningful and effective approach to RRI will have to integrate and balance substantive and procedural elements"

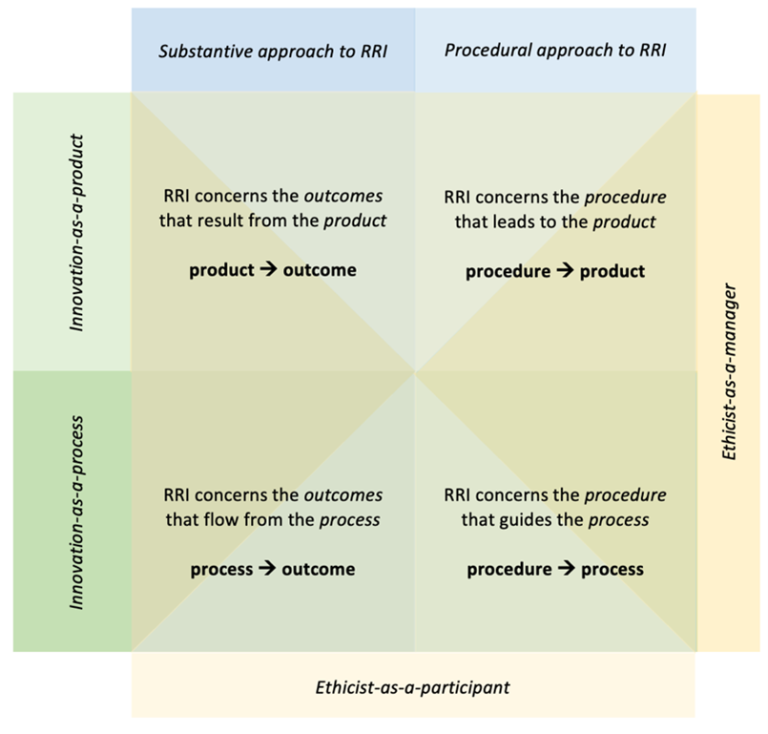

Adjacent to the issues discussed above is the question about the role of ethicists in contributing to RRI. Here too, roughly two perspectives can be distinguished. The role of the ethicist can either be considered as primarily substantive or as procedural. In the first case, the ethicist articulates an important voice in the discussions about how to guide research and innovation in a value-sensitive manner. This can be called the ethicist-as-a-participant role. In the second case, the ethicist acts as a facilitator of such discussions and a moderator of possible value conflicts. We can refer to this as the ethicist-as-a-manager role. Acknowledging that something like ethical expertise exists – which should not be conflated with placing ethicists on a moral high ground –arguments can be made for both views.

Although the role of ethicists in the context of RRI is not self-evident, it is rarely explicitly reflected on. To invoke this reflection, we should update the previous RRI matrix by including the two perspectives on the role of the ethicist in RRI practice. This way, the RRI matrix can serve as a useful reflection tool for thinking about a meaningful, contextual approach to RRI.

Figure 2. Revised RRI matrix

About the author

Eline de Jong is a PhD candidate on the Philosophy and Ethics of Quantum-Safe Cryptography at the Institute for Logic, Language and Computation, and the Institute of Physics (University of Amsterdam). Her current research focuses on the societal impact of quantum technologies (eg. Own the Unknown: An Anticipatory Approach to Prepare Society for the Quantum Age; and Towards Responsible Quantum Technology). Previously, Eline worked at the Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR) as a member of the research project on the societal impact of Artificial Intelligence. She is co-author of the resulting policy advisory report ‘Mission AI: The New System Technology’. Eline also took part in the Dutch working group that developed the Exploratory Quantum Technology Assessment, a tool for exploring the ethical, legal and societal aspects of quantum applications.