Dependency is an inherent feature of human existence. At various stages in our lives, we will inevitably have needs and desires that we cannot meet on our own. As infants, we depend on our parents; as patients, we depend on our doctors; as students, we depend on our teachers. It is within these asymmetrical relations of dependency —where we find ourselves vulnerable relative to whom we are related to— that care theorists advocate for care as a value and practice that “expresses the ethically significant ways in which we matter to each other” (Bowden, 2002, p. 10).

The rationale for care is simple: “When genuine needs and legitimate wants go unmet; when our concerns elicit only indifference; when human connections are broken through exploitation, domination, hurt, neglect, detachment, or abandonment”, moral harm ensues (Kittay, 2019a, p. 178). Care is needed to prevent these harms.

But today, humans don’t just depend on other humans. We also depend on technology. Technology in many ways exists to meet our needs and desires as modern creatures. Our ability to communicate and connect, to navigate our surroundings, to be safe, to stay healthy and live well, is often enabled by technology. We depend on technology, and given our commitment to technological advancement and its numerous benefits, this dependency is only set to run deeper. If we agree that care is a value that should inform dependency relations, is there also a moral duty for care to inform our relation to technology given our increased dependence on it?

Imagine being a first-time tourist in the Netherlands, having just spent a week exploring the country. The night before your departure, you buy your train ticket to Schiphol Airport for your journey back home. Upon arriving at the station the next day, you learn that all trains to Schiphol have been canceled. In a panic, you embark on an exhaustive Google search for alternative routes to catch your international flight, draining your phone’s battery. You soon realize that no other mode of transportation will get you to Schiphol on time and, in desperation, you resort to the popular ride-hailing app Uber.

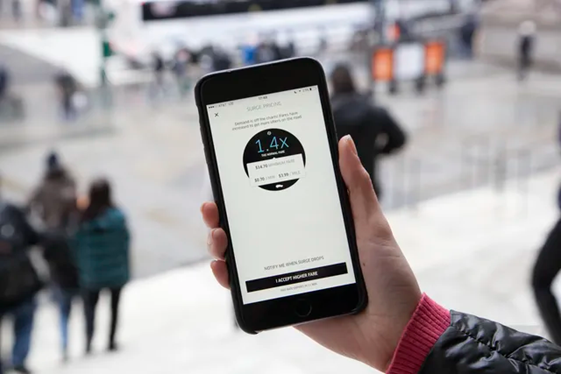

You brace yourself for a pricier Uber due to high demand, but unknowingly to you, your low phone battery adds a surcharge to your ride. Capitalizing on riders’ vulnerability, Uber has been accused of hiking up the price of the trip if the rider’s battery is low (Chowdhry 2016, Vice Staff 2023, Udvarlaki 2021, Lindsay 2019).

Photographer: Amelia Krales for The Verge

This is an example of how our dependence on technology opens us to exploitation, especially at the hands of those designing it. After all, the Uber platform can only hike up prices based on battery percentage if it has been programmed to do so. Similar concerns have been raised with social media algorithms, pharmaceuticals, or medical devices, where user dependency is not only exploited, but purposefully engineered to become more and more entrenched over time. Our dependence on technology makes us dependent on designers, and, in the face of this dependency, we want to know that we are being looked after rather than exploited, neglected, or actively harmed.

This might lead us to conclude that the best answer is to ease dependency in the interest of equality. This has often been thought of as a task for justice rather than care. By pushing for practices such as participatory design, justice aims for users to have a greater say in how technology is designed; to express our needs and wants and have these be reflected in the design process and outcomes. In other words, justice seeks to prevent exploitation by leveling uneven powers, in this case, between users and designers.

Care theorists agree that reducing asymmetrical dependency reduces the opportunity for exploitation (and other moral harms). However, they contend that it is not always possible to eliminate all dependencies, and “it is far from clear that we would want to, were it in our power to do so” (Lovett, 2010, p. 53). As infants, patients, and students, our dependence on our caregivers makes room for attentiveness, trust, and affection, for the expression of the “ethically significant ways in which we matter to each other” (Bowden, 2002, p. 10), especially when at our most vulnerable.

Similarly, depending on technology allows for many of our needs and desires to be met creatively and ever-more efficiently by designers, who possess a unique toolkit to do this. Why should relying on their specialized skill inexorably risk exploitation, neglect, or harm? Shouldn’t users be able to trust designers the same way an infant should trust their parent, a patient their doctor, or a student their teacher?

This does not mean that justice and care cannot coexist as values relevant to technology and design. Quite the contrary. In order to be cared for, we must all have a platform to be heard, to articulate our particular needs and desires. Designing for justice can provide just that by reducing the power imbalance between users and designers and increasing the say of users. But care pushes us to be attentive to these needs and desires and foster relationships of trust and respect, especially in circumstances where dependency may not be as easily reduced. To that end, care and justice are aligned.

Unfortunately, we rarely think about our relation to technology —and thereby designers— as one of dependency where there may be room for care. It is this simple realization that motivates us to advocate for care as a value that ought to mediate this relation. Designing with care allows us to mitigate moral harm, foster relationships of trust, and empower designers to use their skills to express caring ingenuity.

References

Bowden, P. (2002). Caring: Gender-Sensitive Ethics. Routledge.

Chowdhry, A. (2016, May 25). Uber: Users Are More Likely To Pay Surge Pricing If Their Phone Battery Is Low. Forbes.

Kittay, E. F. (2019a). An ethics of care. In Oxford University Press eBooks (pp. 164–183). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190844608.003.0009

Kittay, E. F. (2019b). Dependency and disability. In Oxford University Press eBooks (pp.143–163). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190844608.003.0008

Lindsay, J. (2019, September 27). Does Uber charge more if your battery is lower? Metro.

Lovett, F. (2010). A general theory of domination. Oxford University Press.

Udvarlaki, R. (2021). How your battery percentage can influence your Uber ride cost: report. Pocketnow.

Vice Staff, (2023, April 11). Uber Accused of Charging People More If Their Phone Battery Is Low. Vice.